The Role of Fisheries in Nigeria’s Blue-Economy Policy Agenda

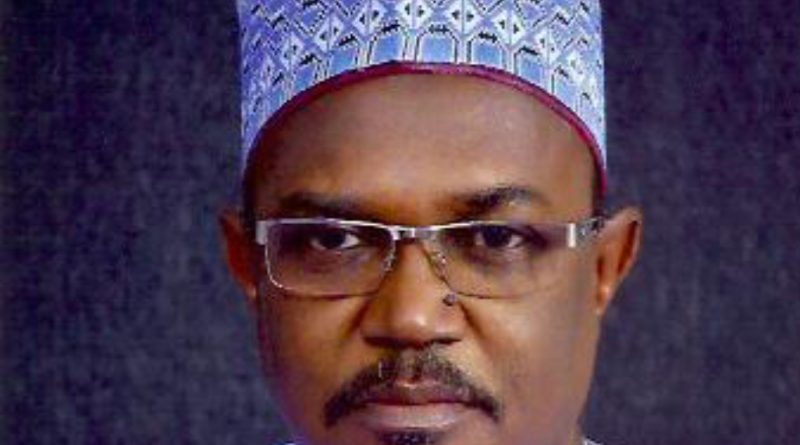

Abba Y. Abdullah

In his recent pronouncement, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu created the Ministry of Marine and Blue Economy as one of the paradigms shifts to the economic development of Nigeria. According to the World Bank, the blue economy is the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of the ocean ecosystem. UN also defines blue economy as “a range of economic activities related to oceans, seas, and coastal areas and whether these activities are sustainable and socially equitable”. However, the SDGs Goal No. 14 describe the blue economy as “life below water, i.e., marine, coastal, and inland lakes, reservoirs, and rivers in general.

In Nigeria, there is the marine, coastal (brackish) and three principal drainage systems in Nigeria: the Niger Basin, the Chad Basin, and the West Coastal Basin. The largest of the three is the Niger system which includes the Benue River. The catchment area of the Niger/Benue system covers about 575,500 km sq. which is about 60% of the country. There are currently 723 reservoirs with a recorded area of not less than 5,628 km sq. in Nigeria. Marine water resources are taken to include brackish water eco-systems and marine waters. This ranges from marine/coastal water to the EEZ offshore waters with an estimated area of 221,300 km sq.

Among the major economic activities envisage in the blue economy include fisheries, coastal leisure and tourism, ship and boat building, offshore oil and gas and shipping (marine transportation), blue carbon sequestration, offshore renewable energy, deep sea mining and biotechnology, fisheries stand out as the most promising in terms of equitable opportunities in investment and highest in job creation.

The recently appointed Minister of Marine and Blue Economy, Adegboyega Oyetola estimated that the blue economy could yield up to N7 trillion per annum. Fisheries could contribute up to 20% if properly managed.

The fisheries sector contributes 1.16 percent to the National GDP in 2021 and 0.47 percent in the year 2022. The country’s aquatic food systems’ contribution to the gross domestic product rose from 0.5 percent in 2013 to 4.5 percent in 2021. Over 1.48 million individuals are reportedly engaged in the fisheries sector in Nigeria. In 2016, 653,000 individuals were engaged in inland fisheries, while an estimated 21 percent of them are women. Nigeria’s blue economy therefore remains one of the country’s anchor sub-sectors, with maritime trade contributing 1.6 per cent and fisheries contributing 3-5 per cent to the GDP.

Nigeria’s fish resources are derived from three subsectors: The fresh water (inland) fishery, the marine fishery and aquaculture. Over 70 percent of Nigeria’s total domestic fish supply originates from artisanal or small-scale fishers from coastal areas, creeks and lagoons, inland rivers, and lakes. Capture fisheries is dominated by the artisanal fishers (coastal and inland) and a significantly low contribution from industrial vessels and trawlers which basically are coastal fishers. Industrial fishing contributes the least (1%). Inland capture fisheries account for 45 percent of total capture fisheries.

However, inland capture fisheries are in decline which could be reversed if environmental and security challenges are taken care of. For example, the extensive dams built across Nigeria has caused an estimated loss of between 85,000t to 130,000t of annual fish production. Much of this “lost” fish production can be regained by changing the way that water resources are managed. There is also an opportunity to increase fish production from large and medium-sized reservoirs by exploiting the under-utilised open-water pelagic zone of these water bodies. This can be achieved by undertaking a preliminary national survey of reservoirs to identify those waters suitable for stocking with indigenous planktivorous clupeids (sardines).

The marine coastal fisheries of Nigeria owe their productiveness to the enormous beneficial effect of the huge Niger delta which brings nutrients into the area, creating a nursery ground and breeding area for large stocks of finfish and crustaceans. Official statistics of coastal production, both artisanal and commercial, are around 200,000 tons of fish and up to 10,000 tons of shrimp. Actual production may be up to 50% higher, as reported in a recent survey.

It is pertinent to note that the area of operation of the marine artisanal fleet is also the area of marine operation of all the petroleum extraction companies in the country. The oil extraction installations, namely rigs, wells, terminals, gas flare stations, and pipelines, are scattered across the Niger delta coast, from the lagoons to waters of 70 meters depth, 30 miles offshore. The bulk of the installations occur in the coastal belt within 15 miles of the beach. It has been estimated that a total of 2,800 square kilometers of the coastal sea area has been commandeered by the oil industry for its extraction facilities. The coastal fishery may be losing potential annual catches of up to 28,000 tons through the loss of access to these areas of the seabed where demersal stocks are found.

In addition to the physical presence of the oil installations, is the more serious constraint to fish resource sustainability, posed by the continuing amount of pollution from oil spills, leaks, and discharges, from the wells, pipelines, and terminals. Many of the serious leaks, and dumping of oil and toxic waste, occurs in the creeks and lagoons, and may be resulting in juvenile fish mortality and spawning problems for coastal stocks. The effect may be reducing the number of fish surviving to maturity by over 30,000 or 40,000 tons a year.

There are other fish species with very high economic potential which has hitherto been ignored or unexploited. Tuna, the primary commercial species with the highest values, skipjack, yellowfin, and bigeye have been reported to occur in Nigerian waters within 30 km of the coast from December to May. They are reported to be further from the coast during other months of the year. This range is within the current operating distance of the current industrial trawler fleet. If the scientific data is correct and practical commercial quantities prove to be available, it is very likely that relatively inexpensive tuna fishing practices used in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean can be used successfully off the coast of Nigeria.

There is also a large opportunity to harvest fish for production of fishmeal for animal feed. The stocks of fish in deep water offshore include the drift fish Ariomma spp. and the mesopelagic lantern fish which occur in enormous quantities in the Gulf of Guinea. The stocks have been identified by FAO, NORAD, and NIOMR, but have not been extensively fished except by foreign trawlers. It was estimate that there could be a maximum sustainable yield of 2,000,000 t/yr, producing 400,000t of fish meal, worth around $300-500 million/yr.

Aquaculture: From early 2000s to 2015, aquaculture has recorded the fastest growth rate among the subsectors contributing the total domestic fish production in Nigeria with a percentage rise in growth from 6% in 2003 to 20% in 2015. Aquaculture contributes 25 percent of total fish production in the last 3 years (2019-2021) (FAOSTAT). Cage culture in both inland and marine waters, sea ranching could double or even triple aquaculture contribution to domestic fish production as well as the tuna export.

From the aforementioned, it is obvious the fisheries economy is one of the key sectors of the blue economy but quite often overlooked and emphasis is given to oil exploitation, shipping and other marine extractive activities. It should be noted that the biological aspect of the blue economy, i.e., fisheries and other marine species bear the brunt of environmental impact from the other activities within the blue economy ecosystem (oil extraction, shipping, etc.). Therefore, to sustaining the marine and freshwater ecosystems could only be attain of the life below water is maintain and sustain for ecosystem equilibrium.

Fisheries development within the blue economy could be sustainably managed by taxing oil and gas, shipping and other activities and a bio-blue economy fund should be established to warehouse the tax funds. This will ensure the maintenance of the teaming jobs in the sector as well as clean and sustainable marine and freshwater ecosystems for the attainment of the blue economy policy. One of the low hanging fruits for the attainment of this strategy is the establishment of Nigeria’s Fisheries Commission as outlined in the drafted Nigeria’s Fisheries Act 2014 funded by the European Economic Commission. The drafted Act is ready for legislative action and the Ministry for Marine and Blue Economy could take it up and update to reflect the current policy objectives of the current administration of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu.

Abba Y. Abdullah, PhD.

aquagric@gmail.com