THE THIN LINE BETWEEN PROTEST, DEMONSTRATION, and RIOT: A Nigerian Odyssey

By Dr. Iyke Ezeugo_

“A Prelude in Irony”

In the annals of Nigerian history, the line between a protest, a demonstration, and a riot is as thin as a strand of hair, often blurred by the very masses firing the action and the forces meant to safeguard the nation. From the colonial era to the present-day democratic experiment, this line has been trodden upon by activists, politicians, hired crowds, aggrieved citizens, and opportunists alike, each leaving an indelible mark on the country’s socio-political landscape.

Let’s examine some historical context, from Colonial Chains to Post-Colonial Pains:

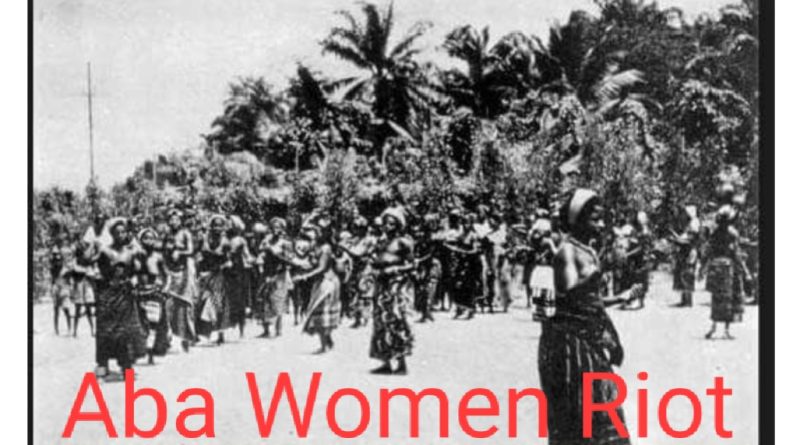

The Aba Women’s Riot of 1929

Although it has been misnamed *”Aba Women’s RIOT”,* this was never planned to be a riot. The Aba Women’s riot was a seminal *PROTEST* against colonial taxation. These valiant women, armed with nothing but their voices and tenacity, not with planks, machetes and guns, managed to overturn oppressive policies. The British, of course, labeled it a “riot” to justify the violent suppression that followed. Ironically, it laid the groundwork for future demonstrations, teaching Nigerians that collective action could indeed challenge the status quo. However, this is what self-serving power-drunk politicians will never allow to happen: They will do everything possible to rebrand it, thwart it, hijack and derail it. Government does this through direct response to the matter before the proposed protest date, public enlightenment, and or other forms of state intelligence and security machinations including information manipulation, threats, intimidation, blackmail, and *heavy-handed response* using both non-state and state actors.

The 1945 General Strike

As World War II ended, Nigerian workers, emboldened by the global push for independence, demanded better wages and working conditions. The strike, though peaceful, was met with a heavy-handed response. Yet, it sowed seeds of labor activism that would later bloom into full-fledged riot and later political movements.

The Ali Must Go Protests of 1978

Fast forward to the military era, when students nationwide rose against General Olusegun Obasanjo’s military regime’s education policies. What began as a peaceful demonstration morphed into chaos as state forces unleashed violence on unarmed students. *The aftermath was tragic,* but it cemented the students’ role as a formidable force in Nigeria’s political arena even though this could still be achieved without the colossal damages and loss of lives that followed the event.

The #EndSARS Movement: A Modern-Day Paradox

In October 2020, the #EndSARS protest erupted, demanding the disbandment of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) known for brutality and extrajudicial killings. It started as a social media campaign, quickly escalating into nationwide demonstrations. *The line between protest and riot blurred when peaceful protesters at Lekki Toll Gate were allegedly met with live bullets,* a grim reminder of the state and their enemies’ propensity for violence.

The Brewing #EndBadGovernment Protest

The proposed #EndBadGovernment protest is a sequel to #EndSARS, with broader demands for governance reforms. The triggers are multifaceted: rampant corruption, economic hardship, and a general sense of disillusionment with the political class. Participants range from disenchanted youths to civil society groups, each with varying degrees of understanding and expectations.

Arguments for Holding the Protest

1. Accountability:

Protests shine a spotlight on government failings, compelling officials to address grievances.

2. Civic Engagement:

It galvanizes citizens to participate actively in governance, fostering participatory governance and a culture of accountability.

3. Public Awareness:

Brings critical issues to the forefront, educating the masses about their rights and the government’s responsibilities.

Arguments Against Holding the Protest

1. Risk of Violence:

Given Nigeria’s history and current state of despondency resulting from the biting economic hardship, *peaceful protests can quickly devolve into chaos,* resulting in loss of life and property.

2. Hijacking by Miscreants:

Protests can be infiltrated by elements with ulterior motives, detracting from the original cause.

3. Government Crackdown:

The state’s typical response to dissent is often brutal, and the masses’ resistance will be violence, leading to widespread human rights abuses, irrecoverable damages, and unwarranted loss of lives.

Government’s Response: Palliatives and Propaganda

The demand is on the Federal Government. In a bid to stave off the protest, the government has rushed out palliatives and disseminated information about financial aid and allocations to states and local government. These measures, however, reek of superficiality and fail to address the root causes of discontent. The palliatives are often ill-timed, inadequate, misdirected, and mismanaged, while the purported financial aid rarely trickles down to the common man.

CRITIQUE

Shortcomings of the Government’s Approach

– Superficial Solutions:* Palliatives address symptoms rather than root causes.

– Lack of Transparency: Both the material and financial aid announcements lack clarity on implementation and monitoring.

– Disconnect with Reality: Policies often reflect a disconnect from the lived experiences of ordinary Nigerians; the ostentatious and wasteful lifestyles like the purchase of yachts, additional private jets, and fleets of vehicles for the president, and the Armored SUVs for members of the National Assembly, the budget padding, and the wanton corruption.

Moderating Expectations

– Realism: The demanding masses must temper their expectations, recognizing that systemic change is a gradual process.

– Constructive Engagement: Dialogue and negotiations should complement protests to achieve sustainable outcomes. A practical example is what Brekete Family, Human Rights Radio, and Television Abuja is doing to hold government accountable and demand answers without relenting. A few media houses and journalists across the country are also doing well in this intellectual protest, and there are visible results (howbeit slowly) of their individual works and the aggregate effects are evident in the responses so far seen. A typical example is the sudden backtrack of the federal government to lose their grips on the neck of Dangote Refinery and Presidential order to sell crude oil to the Refinery on local currency (naira) for 6 months, the rushed palliatives, and the announced readiness to engage and adjust.

Bola Ahmed Tinubu: The Protester Turned President

It is worth noting the irony that the current president, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, was himself once a protester. Tinubu was an active participant in the pro-democracy struggles of the 1990s, notably during the June 12 protests against the annulment of the presidential election won by MKO Abiola. He also joined in different protests after that. His role in these historic protests lends a certain irony to the current situation.

However, the goal today is not to pay Tinubu with his own coin but to focus on the purpose, approach, and soul of the nation. The #EndBadGovernment protest is not a vendetta but a cry for genuine reform and a better Nigeria.

Alternative Approaches and Predictions

From all indications, if the protest proceeds as planned, there is a high risk of escalation into violence, potentially leading to significant loss of life and property. This scenario, while tragic, is not inevitable. Alternative approaches could include:

1. Structured Dialogue: Establishing a framework for continuous dialogue between the government and civil society.

2. Incremental Reforms: Focusing on achievable, short-term reforms as stepping stones to broader change.

3. Community-Based Initiatives: Empowering local communities to spearhead development projects, reducing reliance on central government interventions.

The Endgame

The thin line between protest, demonstration, and riot in Nigeria is a testament to the nation’s turbulent history and the resilience of its people. While protests are a vital tool for demanding accountability and change, they must be approached with caution and a clear strategy to avoid the pitfalls of violence and hijacking. The proposed #EndBadGovernment protest embodies the frustrations of a populace yearning for better governance, but it also underscores the need for realistic expectations and constructive engagement to achieve lasting change. In the words of Martin Luther King Jr., “A riot is the language of the unheard.” It is up to both the government and the governed to ensure that this language does not descend into chaos but rather translates into meaningful action.

The Power of the Fourth Estate

The role of the media, the fourth estate of the realm, in these dynamics cannot be overstated. The press has historically been a powerful tool for civic engagement and holding governments accountable. In Nigeria, the media has often been at the forefront of highlighting injustices and rallying public opinion. For instance, during the #EndSARS movement, platforms like Twitter and various news outlets were instrumental in spreading awareness and organizing protests. *Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie* remarked during an interview, “The media is a powerful tool in the hands of those who understand its true purpose: to inform, educate, and hold power accountable.

The delicate balance between protest, demonstration, and riot in Nigeria’s socio-political landscape underscores the complexity of civic activism in a volatile environment.